Can We Prevent Persistent Occiput Posterior Babies?

By: Henci Goer, BA | 0 Comments

Today, regular contributor Henci Goer, co-author of the recent book, Optimal Care in Childbirth; The Case for a Physiologic Approach, discusses a just published study on resolving the OP baby during labor through maternal positioning. Does it matter what position the mother is in? Can we do anything to help get that baby to turn? Henci lets us know what the research says in today's post. - Sharon Muza, Community Manager

_________________________

In OP position, the back (occiput) of the fetal head is towards the woman's back (posterior). Sometimes called 'sunny side up,' there is nothing sunny about it. Because the deflexed head presents a wider diameter to the cervix and pelvic opening, progress in dilation and descent tends to be slow with an OP baby, and if OP persists, it greatly increases the likelihood of cesarean or vaginal instrumental delivery and therefore all the ills that follow in their wake.

Does maternal positioning in labor prevent persistent OP?

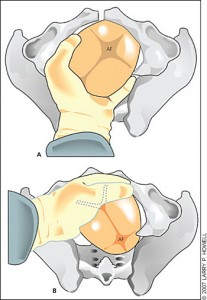

This month, a study titled 'Is maternal posturing during labor efficient in preventing persistent occiput posterior position? A randomized control trial' reported on the use of maternal positioning in labor to rotate OP babies to occiput anterior (OA). Investigators randomly allocated 220 laboring women with OP babies either to assume positions designed to facilitate rotation or to recline on their backs. The positions were devised based on computer modeling of the mechanics of the woman's pelvis and fetal head according to degree of fetal descent. The position prescribed for station -5 to -3, i.e., 3-5 cm above the ischial spines, a pelvic landmark, had the woman on her knees supporting her head and chest on a yoga ball. At station -2 to 0, i.e., 2 cm above to the level of the ischial spines, she lay on her side on the same side as the fetal spine with the underneath leg bent, and at station > 0, i.e., below the ischial spines, she lay on her side on the same side as the fetal spine with the upper leg bent at a 90 degree angle and supported in an elevated position.

The good news is that regardless of group assignment, and despite virtually all women having an epidural (94-96%), 76-78% of the babies eventually rotated to OA. The bad news is that regardless of group assignment, 22-24% of the babies didn't. As one would predict, 94-97% of women whose babies rotated to OA had spontaneous vaginal births compared with 3-6% of women with persistent OP babies. Because positioning failed to help, investigators concluded: 'We believe that no posture should be imposed on women with OP position during labor' (p. e8).

Leaving aside the connotations of 'imposed,' does this disappointing result mean that maternal positioning in labor to correct OP should be abandoned? Maybe not.

Of the 15 women with the fetal head high enough to begin with position 1, no woman used all 3 positions because 100% of them rotated to OA before fetal descent dictated use of position 3. I calculated what percentage of women who began with position 2 or 3, in other words fetal head at -2 station or lower, achieved an OA baby and found it to be 75% - the same percentage as when nothing was done. What could explain this? One explanation is that a position with belly suspended is more efficacious regardless of fetal station, another is that positioning is more likely to succeed before the head engages in the pelvis, and, of course, it may be a combination of both.

Common sense suggests that the baby is better able to maneuver before the head engages in the pelvis. If so, it seem likely that rupturing membranes would contribute to persistent OP by depriving the fetus of the cushion of forewaters and dropping the head into the pelvis prematurely. Research backs this up. A literature search revealed a study, 'Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: A retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001' finding that artificially ruptured membranes was an independent risk factor for persistent OP. Returning to the trial, all women had ruptured membranes because it was an inclusion factor. One wonders how much better maternal positioning might have worked had this not been the case, and an earlier trial offers a possible answer.

In the earlier trial, 'Randomized control trial of hands-and-knees position for occipitoposterior position in labor,' half the women had intact membranes. Women in the intervention group assumed hands-and-knees for at least 30 minutes during an hour-long period while the control group could labor in any position other than one with a dependent belly. Twelve more women per 100 had an OA baby at delivery, a much bigger difference than the later trial. Before we get too excited, though, the difference did not achieve statistical significance, meaning results could have been due to chance. Still, this may have been because the population was too small (70 intervention-group women vs. 77 control-group women) to reliably detect a difference, but the trial has a bigger problem: fetal head position at delivery wasn't recorded in 14% of the intervention group and 19% of the control group, which means we don't know the real proportions of OA to OP between groups.

Take home: It looks like rupturing membranes may predispose to persistent OP and should be avoided for that reason. The jury is still out on whether a posture that suspends the belly is effective, but it is worth trying in any labor that is progressing slowly because it may help and doesn't hurt.

Does maternal positioning in pregnancy prevent OP labors?

Some have proposed that by avoiding certain postures in late pregnancy, doing certain exercises, or both, women can shift the baby into an OA position and thereby avoid the difficulties of labor with an OP baby. A 'randomized controlled trial of effect of hands and knees posturing on incidence of occiput posterior position at birth' (2547 women) has tested that theory. Beginning in week 37, women in the intervention group were asked to assume hands-and-knees and do slow pelvic rocking for 10 minutes twice daily while women in the control group were asked to walk daily. Compliance was assessed through keeping a log. Identical percentages (8%) of the groups had an OP baby at delivery.

Why didn't this work? The efficacy of positioning and exercise in pregnancy is predicated on the assumption that if the baby is OA at labor onset, it will stay that way. Unfortunately, that isn't the case. A study, 'Changes in fetal position during labor and their association with epidural anesthesia,' examined the effect of epidural analgesia on persistent OP by performing sonograms on 1562 women at hospital admission, within an hour after epidural administration (or four hours after admission if no epidural had been administered), and after 8 cm dilation. A byproduct was the discovery that babies who were OA at admission rotated to OP as well as vice versa.

Take home: Prenatal positioning and exercises aimed at preventing OP in labor don't work. Women should not be advised to do them because they may wrongly blame themselves for not practicing or not practicing enough should they end up with a difficult labor or an operative delivery due to persistent OP.

Do we have anything else?

Larry P Howell

aafp.org/afp/2007/0601/p1671.html

We do have one ray of sunshine in the midst of this gloom. Three studies of manual rotation (near or after full dilation, the midwife or doctor uses fingers or a hand to turn the fetus to anterior) report high success rates and concomitant major reductions in cesarean rates, if not much effect on instrumental vaginal delivery rates. One study, 'Manual rotation in occiput posterior or transverse positions: risk factors and consequences on the cesarean delivery rate,' comparing successful conversion to OA with failures reported an overall institutional success rate of 90% among 796 women. A 'before and after' study, 'Digital rotation from occipito-posterior to occipito-anterior decreases the need for cesarean section,' reported that before introducing the technique, among 30 women with an OP baby in second stage, 85% of the babies were still OP at delivery compared with 6% of 31 women treated with manual rotation. The cesarean rate was 23% in the 'before' group versus 0% in the 'after' group. The third study, 'Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position,' compared 731 women having manual rotation of an OP baby in second stage with 2527 women having expectant management. The success rate of manual rotation was 74% and the overall cesarean rate in treated women was 9% versus 42% in the expectantly managed group.

Manual rotation is confirmed as effective, but is it safe? This last study reported similar rates of acidemia and delivery injury in newborns. As for their mothers, investigators calculated that four manual rotations would prevent one cesarean. The study also found fewer anal sphincter injuries and cases of chorioamnionitis. The only disadvantage was that one more woman per hundred having manual rotation would have a cervical laceration.Take home: Birth attendants should be trained in performing manual rotation, and it should be routine practice in women reaching full dilation with an OP baby.

What has been your experience with the OP baby? Is what you are teaching and telling mothers in line with the current research? Will you change what you say now that you have this update? Share your thoughts in the comment section. - SM

References and resources

Cheng, Y. W., Cheng, Y. W., Shaffer, B. L., & Caughey, A. B. (2006). Associated factors and outcomes of persistent occiput posterior position: a retrospective cohort study from 1976 to 2001. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 19(9), 563-568.

Desbriere R, Blanc J, Le Dû R, et al. Is maternal posturing during labor efficient in preventing persistent occiput posterior position? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;208:60.e1-8. PII: S0002-9378(12)02029-7 doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2012.10.882

Kariminia, A., Chamberlain, M. E., Keogh, J., & Shea, A. (2004). Randomised controlled trial of effect of hands and knees posturing on incidence of occiput posterior position at birth. bmj, 328(7438), 490.

Le Ray, C., Serres, P., Schmitz, T., Cabrol, D., & Goffinet, F. (2007). Manual rotation in occiput posterior or transverse positions: risk factors and consequences on the cesarean delivery rate. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 110(4), 873-879.

Lieberman, E., Davidson, K., Lee-Parritz, A., & Shearer, E. (2005). Changes in fetal position during labor and their association with epidural analgesia.Obstetrics & Gynecology, 105(5, Part 1), 974-982.

Reichman, O., Gdansky, E., Latinsky, B., Labi, S., & Samueloff, A. (2008). Digital rotation from occipito-posterior to occipito-anterior decreases the need for cesarean section. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 136(1), 25-28.

Shaffer, B. L., Cheng, Y. W., Vargas, J. E., & Caughey, A. B. (2011). Manual rotation to reduce caesarean delivery in persistent occiput posterior or transverse position. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 24(1), 65-72.

Simkin, P. (2010). The fetal occiput posterior position: state of the science and a new perspective. Birth, 37(1), 61-71.

Stremler, R., Hodnett, E., Petryshen, P., Stevens, B., Weston, J., & Willan, A. R. (2005). Randomized Controlled Trial of Hands-and-Knees Positioning for Occipitoposterior Position in Labor. Birth, 32(4), 243-251.

Recommended resource: The fetal occiput posterior position: state of the science and a new perspective http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=simkin%202010%20posterior by Penny Simkin.

Published: January 29, 2013

Tags

CesareanLabor ProgressFetal PositioningBack LaborLabor/BirthHenci GoerLearning OpportunitiesEvidence Based TeachingLearner EngagementHands-onImproving teaching skillsPractical skillsInstrumental DeliveryOcciput PosteriorOP Babies