Unintended Consequences: Cesarean Section, The Gut Microbiota, and Child Health

By: Sharon Muza, BS, LCCE, FACCE, CD/BDT(DONA), CLE | 0 Comments

Today's guest post is written by Dr. Mark Sloan, pediatrician and author of Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History and the Wonder of Childbirth. Dr. Sloan takes a look at impact of cesarean birth on normal gut bacteria. - SM

When I first learned some years ago that cesarean section was associated with an increased risk of childhood asthma and eczema, I eagerly awaited the rest of the story. What could the link possibly be? Epidurals? Anesthetics? Antibiotics? Something strange and exotic was afoot, I was certain.

Imagine my surprise, then, when a growing body of evidence pointed to an unexpected source: the newborn gastrointestinal tract and the microorganisms that live there.

How might intestinal bacteria play such a major role in the health and well-being of newborns and children? The answer lies in an ancient, mutually beneficial relationship between humans and bacteria, one that modern birth technology has dramatically altered.

* * *

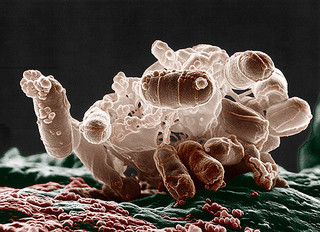

Creative Commons photo by Eric Erbe, Colorization

by Christopher Pooley. USDA

"Microbiota" is the term used to describe the community of microorganisms-bacteria, viruses, and fungi-that normally live in or on a given organ in the body. There's a unique microbiota that inhabits the mouth, for example, another that lives on the skin, and still another that populates the intestine, or gut. Given an intestinal surface area of about 2,700 square feet-more or less the size of a tennis court-the microbiota inhabiting the gut is the largest and most diverse in the body.

How large and diverse? The gut microbiota contains roughly one quadrillion cells-at least ten times as many cells as does the human body itself. More than 1,000 bacterial species having been identified to date, with unknown numbers yet to be discovered.

How do all those bacteria get there? The fetal intestine, in the absence of congenital infection, is sterile in utero. The bacteria that come to colonize the bowel are acquired during birth and shortly afterwards, a process that is very much influenced by how a baby is born.

The gut microbiota and mode of delivery

In vaginally-born babies, the bacteria destined for the gut microbiota originate primarily in the maternal birth canal and rectum. Once these bacteria are swallowed by the newborn, they travel through the stomach and colonize the upper and lower intestine, a complicated process that evolves rapidly.

Infants born by cesarean section-particularly cesareans performed before labor begins-don't encounter the bacteria of the birth canal and maternal rectum. (If a cesarean is performed during labor the infant may be exposed to these bacteria, but to a lesser degree than in vaginal birth.) Instead, bacteria from the skin and hospital environment quickly populate the bowel. As a result, the bacteria inhabiting the lower intestine following a cesarean birth can differ significantly from those found in the vaginally-born baby.

Whatever the mode of delivery, a core gut microbiota is well established within a few weeks of life and persists largely intact into adulthood. A less stable peripheral microbiota-one that is more sensitive to changes in diet and environmental factors, like antibiotics-is created as well. Between one and two years of age, when weaning from breast milk typically leads to a diet lower in fat and higher in carbohydrates, the gut microbiota takes on its final, mature profile.

Development of the newborn immune system

The dramatic first steps in immune system development take place at the same time the core microbiota is being formed, and the gut bacteria play a key role in that process.

In the hours and days following birth, the newly-arrived gut bacteria stimulate the newborn to produce white blood cells and other immune system components, including antibodies directed at unwelcome, disease-causing microorganisms. The bacteria of the microbiota also "teach" the newborn's immune system to tolerate their own presence-to differentiate bacterial friend from foe, in other words.

In a cesarean birth the fledgling immune system is confronted with unfamiliar, often hostile bacteria-including Clostridium difficile, a particularly troublesome hospital-acquired bug. In addition, the healthy probiotic bacteria associated with vaginal birth (e.g., lactobacillus) arrive later and in lower numbers. These changes in the composition of the normal gut microbiota occur during a critical time in immune system development.

The cesarean-asthma theory (in a nutshell)

Here's how cesareans and asthma are likely connected:

Creative Commons

photo by hemangi28

Humans evolved right along with the gut microbiota normally acquired during vaginal birth. When the composition of the microbiota is imbalanced, or unusual germs like Clostridium difficile appear, the immune system doesn't like it. A low-grade, long-lasting inflammatory response directed at these intruders begins at birth, leading to a kind of weakness and "leakiness" of the intestinal lining. Proteins and carbohydrates that normally would not be absorbed from the intestinal contents-including large, incompletely digested food molecules-make their way into the infant's bloodstream.

To make a very long story short, inflammation and the abnormal processing of food that results appear to increase the risk of asthma and eczema-and diabetes, obesity, and other chronic conditions-later in life.

* * *

Normalizing the post-cesarean gut microbiota

Reducing the cesarean rate is an obvious best practice in promoting a healthy gut microbiota. But there will always be a need for cesarean section, and so researchers are starting to focus on "normalization" of the gut microbiota of cesarean-born babies. Although there are as yet no proven therapies, here are some possibilities:

- Probiotics. Though administering healthful probiotic bacteria to correct an imbalanced microbiota makes intuitive sense, studies to date have been disappointing, with only minor, short-lived changes changes to the gut microbiota. However, research into "good" bacteria and how they become established in the intestine is active and ongoing.

- Direct transfer of maternal secretions. Placing maternal vaginal and rectal material into the newborn's mouth has been proposed-more or less mimicking natural colonization-but to date there are no published studies to support the practice.

- Fecal transplantation. Direct transfer of fecal material from healthy adults into the gastrointestinal tracts of people suffering from Clostridium difficile infections has shown promise. Could healthy parents serve as "donors" for their babies? Applying such technology to otherwise healthy newborns is highly impractical at present, to say the least. Still, refinements may someday make this a viable option.

Conclusion

A cesarean section doesn't automatically condemn a child to a lifetime of asthma or eczema, just as a vaginal birth isn't a guarantee of perfect health. But cesarean birth, by altering normal gut microbiota and immune system development, does appear to moderately increase the risk of these and other chronic health conditions. A woman who has the option of choosing her mode of delivery should add this to the many other factors she must weigh in deciding how her baby will be born.

Childbirth educators and other birth professionals, when you speak to your classes or clients about the benefits and risks of cesarean section, do you mention this information. What do you think about this connection? What should your students know about how to minimize the impact of cesarean on the future potential health of their children? Please share your thoughts on the comment section,- SM

Selected references:

1) Effects of mode of delivery on gut microbiota composition

Biasucci G, Rubini M, Riboni S, et al (2010). Mode of delivery affects the bacterial community in the newborn gut. Early Human Development 86:S13-S15

Penders J, Tjhijs C, Vink C, et al (2006). Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in early infancy. Pediatrics 118(2):511-521.

Salimen S, Gibson GR, McCartney AL (2004). Influence of mode of delivery on gut microbiota in seven year old children. Gut 53:1388-1389.

2) Development of the newborn immune system

Huurre A, et al (2008). Mode of delivery: Effects on gut microbiota and humoral immunity.Neonatology 93:236-240.

Johnson C, Versalovic J (2012). The human microbiome and its potential importance to pediatrics. Pediatrics (published online April 2, 2012; DOI: 10.1542/peds2011-2736).

Vael C, Desager, K (2009). The importance of the development of the intestinal microbiota in infancy. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 21(6):794-800

3) Cesarean birth, gut microbiota, and asthma/atopic disease

Azad M, Korzyrkyj A (2012). Perinatal programming of asthma: The role of the gut microbiota.Clinical and Developmental Immunology Volume 2012; Article ID 932072; doi:10.1155/2012/932072

Thanvagnanam S, Fleming J, Bromley A, et al (2008). A meta-analysis of the association between caesarean section and childhood asthma. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 38(4): 629-633.

van Nimwegen F, Penders J, Stobberingh E, et al (2011). Mode and place of delivery, gastrointestinal microbiota, and their influence on asthma and atopy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology128(5):948-955.e3

About Mark Sloan, M.D.

Mark Sloan has been a pediatrician and a Fellow of the American Academy of Pediatrics for more than 25 years. Since 1982, he has practiced with the Permanente Medical Group in Sacramento and Santa Rosa, California, where he was Chief of Pediatrics from 1997 to 2002. He is an Assistant Clinical Professor in the Department of Community and Family Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Sloan's first book, Birth Day: A Pediatrician Explores the Science, the History and the Wonder of Childbirth was published in 2009 by Ballantine Books. His writing has appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Chronicle, the San Francisco Examiner, and Notre Dame Magazine, among other publications. Dr. Sloan can be reached through his blog

.

Published: July 12, 2012

Tags

BreastfeedingCesareanResearchVaginal BirthPediatricianInformed ConsentLabor/BirthMaternal Infant CareBabiesLearning OpportunitiesEvidence Based TeachingMark SloanBacteria