Understanding Methodology: Elements of Experimental Design

By: Andrea D. Lythgoe, LCCE | 0 Comments

In this third series on Understanding Research, we will take a basic look at methodologies that are used in research. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches will be explored, with discussion on the reasons different approaches might be used and the strengths and weaknesses of each. Hopefully this will help you to better understand why the methodologies matter and what you should consider as you read research that helps you to teach and share evidence-based information on topics of maternal and infant health. The first post in the Understanding Methodology can be found here. The second, here. Today we discuss the elements of experimental design. If you would like to review what Andrea has discussed on the blog in the past, to refresh your understanding, please click here. - Sharon Muza, Community Manager

Experimental research: The Pre- and Post-test design

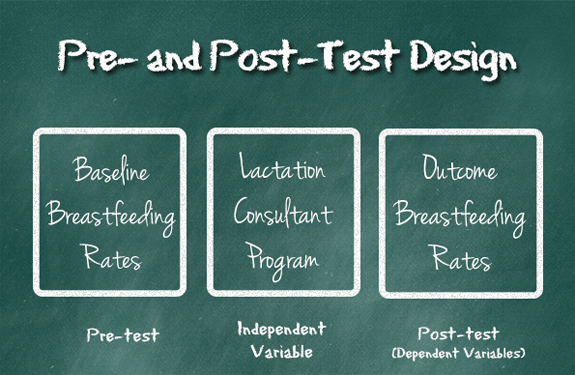

Now that we are ready to talk about specific methods, we'll start with one of the most basic of the experimental designs. The researcher wants to know if a specific thing works. Could be a drug, a procedure, an educational program, or any number of things. Researchers call this thing a variable, and it could be a treatment, an educational program, or a new product. The variable the researcher is testing is the independent variable, or the one the researcher is manipulating. The dependant variables are the outcomes the researcher is looking at.

For the sake of this discussion, let's say it is a new breastfeeding program that a hospital is implementing. This program would send a lactation consultant to the bedside of every mom who delivers in the hospital within 24 hours of the baby's birth. The program is the independent variable.

The hospital will want to choose several measures that might indicate the success of the program. These are the dependent variables, or outcome measures. In our example, the hospital might want to document the breastfeeding rates, number of moms who complain of nipple soreness, and the weights of babies for 3 months just before beginning the program. This would give them a baseline number for what is happening before introducing the program. Then after successfully implementing the program, they would measure the same things for three months afterward, and see if the outcomes are any different.

The hospital could then compare the two rates to see if the new program improved breastfeeding outcomes.

This basic format can give good results, but there are some issues. One threat to the validity of the study is that other things could happen over the course of the study that could impact breastfeeding rates. If, for example, a new store selling breastfeeding items opened up nearby and the owner offered free breastfeeding courses that were very popular, that could have some effect on breastfeeding successes as well, making the hospital program look better than it really is.

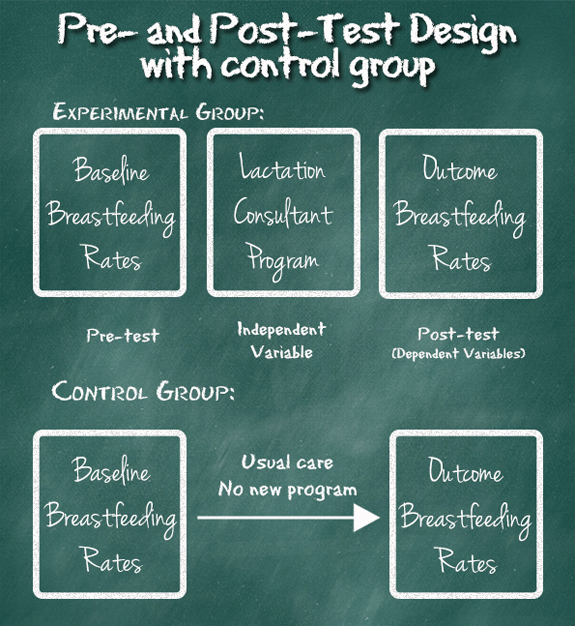

Most researchers will add a control group to this design in order to try and avoid issues of events that could confound the results. In this example, the hospital might do the pretest as before, monitoring the data for 3 months before introducing the new lactation program, then offer the program to HALF the women birthing at the hospital. The women should randomly be divided between those who receive the program and those who receive the usual support provided before the program began. It would look more like this:

In this way of doing the study, any event that happens along that way that could confound the results would likely happen to both groups, and there is a greater chance that the difference between the two groups is in fact due to the new lactation program.

Ethically, researchers cannot always let the control group have no intervention. For example, if you wanted to do a study on the effectiveness of a new way of resuscitating newborns, you cannot ethically let the control group go without any treatment. In these cases, researchers will test the NEW treatment against the current way of doing things.

You could even have more than one experimental group. Maybe the hospital could have a group that gets no lactation program, a group that gets the program on request only, and a group that always gets the lactation program. Knowing if the program works just as well when it is available on request might make a difference in how the hospital implements the program.

The more groups you have, the larger the sample size you need to get significant results, so researchers will make the decision very carefully, keeping in mind logistic and budgetary concerns as well as what they would like to discover with their research.

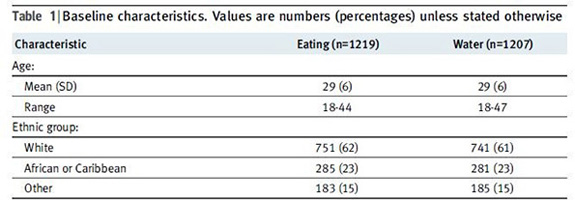

When doing a study with a control or comparison group, researchers need to be able to show that there are not any significant differences between the two groups that could account for the difference. You'll often find tables like this one (O'Sullivan, 2009) showing the demographic makeup of the two groups.

While it would be nice to have identical groups, life is not usually that perfect and the groups will likely have some differences. The chart above shows two groups that are not identical, but are pretty close in the characteristics listed.

Many of the studies you see will have some variation on this basic design. We'll talk further about specific experimental designs in the next segment of our series.

Sources:

Creswell, J. (2009) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. (3rd edition)

Greenhalgh, T. () How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine (4th ed.).

O'Sullivan, G., Liu, B., Hart, D., Seed, P. & Shennan, A. (2009) Effect of food intake during labour on obstetric outcome: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 338:b784. doi:10.1136/bmj.b784.

Rees, C. (2003). Introduction to Research for Midwives (2nd ed.). London. Elsevier Limited.

Published: July 01, 2013

Tags

Childbirth educationMaternal Infant CareAndrea LythgoeUnderstanding ResearchGuest PostsUnderstanding Methodologies