The Maternal Quality Landscape-Part Three, Segment Three: How do we measure AND achieve it?

By: Christine H Morton, PhD | 0 Comments

How Hospitals Measure ED < 39 Weeks

Next we discuss how hospitals actually compile the data elements needed to calculate their rate of elective deliveries occurring between 37 and 39 completed weeks gestation. It is crucial to remember that successful quality measurement depends on the local practices of collecting data, making calculations, and reporting data to quality improvement organizations. Each hospital and unit presents a different configuration of personnel, technology, documentation practices, and other resources, thus conducting measurements in practice may look quite different from one context to the next. As we noted in our first post, maternal quality measures are fairly recent. Hospitals have long reported on measures but obstetrics departments may not have the staff or training to do the work necessary to accurately collect and report on the newer maternal quality measures. Obstetrics has long been considered an "island" in the hospital, with little crossover in terms of staff or patient population, and thus may not have much experience working with the quality department. To further complicate the situation, it turns out that there are several dilemmas faced by hospitals, providers, and quality analysts as they perform the local practices of quality measurement.

Measure Specifications

The Joint Commission publishes the specifications for calculating the perinatal quality measures. The premise of the <39 weeks measure is to calculate a percentage by dividing the number of women who had elective deliveries between 37 and 39 weeks (the numerator) by the total number of women who had elective deliveries (the denominator). One basic sequence of steps in calculating the measure is:

1) Identify births to all mothers between 8 and 65 years old who were not part of clinical trials;

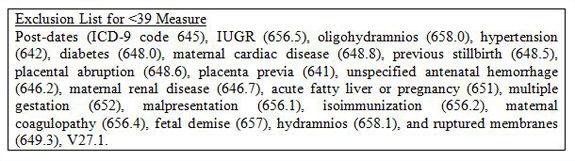

2) Exclude all mothers with an ICD-9 code on the exclusion list (see box);

3) Exclude all mothers where the birth occurred at less than 37 or more than 39 completed weeks gestation;

4) Of those identified so far, include those mothers who had a cesarean section or induction of labor by ICD-9 code.

5) By chart review, exclude those labor inductions or cesarean deliveries done after spontaneous rupture of membranes and/or active labor.

Five steps doesnt seem so bad! However, calculating the measure in practice can be quite tricky. In most hospitals, the data elements needed for each step are found in the patient discharge database containing ICD-9 codes, the birth certificate and/or the delivery logbook and the actual medical chart. Assembling all these sources of information can be challenging, as we describe below.

Deciding on exclusions

There are a number of reasons that elective delivery between 37 and 39 weeks may be medically indicated. The Joint Commission lists such "exclusions" in its specifications manual and the most recent of these are noted in the box. These cases are "exclusions" to the denominator- they must be pulled out before the calculation is made. Although it is possible to identify and list a number of likely scenarios that would be appropriate to exclude, it is impossible to account for every possible scenario that may make early delivery an appropriate choice. This is acknowledged as an issue by the authors of the <39 Weeks Toolkit:

For the purposes of creating a quality measure that was not overly labor intensive to collect, TJC chose to utilize diagnoses that had ICD-9 codes no matter if some codes were over-inclusive (gestational diabetes) or simply not available (prior vertical cesarean section scar). TJC has noted during private conversations with CMQCC leaders that the list of codes is not exhaustive and anticipates that every hospital will have some cases of medically justified elective deliveries prior to 39 weeks that are not on the TJC list. Therefore, each hospital, hospital system or perinatal region should, based on the available evidence, set their own internal medical standards for conditions that justify a scheduled delivery prior to 39 weeks. Note that too loose an internal standard will become apparent once hospitals are publically compared (Main et al, 2010).

Thus, it is up to hospitals to develop their own list of exclusions and decide in unusual cases whether early elective delivery was justified or not. Quality advocates work under the assumption that sloppy or inaccurate measurement practices will be reflected in the data but not until the measure is collected and rates publically reported will it become obvious if a hospital has set too loose a standard for medically-justified elective delivery.

[Tomorrows post will look at data collection and reporting, and the pitfalls that sometimes occur in the process. To read segment one go here. To read from the beginning of this series, go here.]

Posted by: Christine Morton, PhD and Kathleen Pine, University of California, Irvine

Published: December 28, 2011

Tags

Lamaze EducatorsMaternity CareMaternal Infant CareMaternity Care QualityCMQCCKathleen PineMaternal Quality ImprovementNational Quality ForumOnline StoreBan On Elective Deliveries Before 39 WeeksChristine Morton PhDMaternal Quality Care