The Importance of Understanding and Eliminating Disparities in Maternal Health Outcomes

By: Christine H Morton, PhD | 0 Comments

Today's post is by regular Science & Sensibility contributor, Christine Morton, PhD, who is a medical sociologist and has researched and written about disparities in maternal health for many years. Today, Christine takes a look at why women of color in the United States are facing a widening gap in maternal mortality and what some of the underlying factors might be. This is part one of a two part series that looks at the research and examines what might need to change. - SM

Maternal mortality is associated with the widest and most persistent disparity (inequality) in all of public health. African American women have a three to four-fold greater chance of dying as a result of pregnancy than women in any other racial-ethnic group.1 The gap between maternal mortality in African American women and women of other racial-ethnic groups is greater today than it was in the 1940s.2

Photo image creative commons Seattle

Municipal Archives

Yet despite multiple studies over the past several years demonstrating this widening gap, experts today commonly state that reasons for this disparity are 'not fully understood,' and 'limited data exist' to explain why they continue to occur. What is clear, however, is that disparities in maternal deaths are likely to increase, as the proportion of childbearing women who self-identify as members of a racial or ethnic minority group (i.e., non-white) increases in the next decades. Indeed, whether to call these women 'minority' is in question: In May 2012, the Census Bureau reported for the first time that non-Hispanic whites now account for a minority of births in the U.S.

Debates over maternal quality cannot ignore these trends. Are public health and obstetric perspectives providing us with the best paradigms for understanding and reversing disparities in maternal health outcomes?

Let's consider this by examining two recent publications looking at the issue from slightly different perspectives. In the first, Andreea A. Creanga, MD, PhD and her colleagues from the CDC Division of Reproductive Health examined data from 52 reporting areas (50 states, New York City and Washington, DC).3 This Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System consists of de-identified copies of death certificates for all deaths occurring during or within one year of pregnancy (regardless of cause of death) as well as matching birth or fetal death certificates if available.

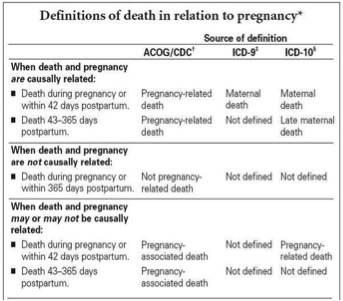

Figure 1: Definitions of Death in Relation to Pregnancy (4)

The Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System used by the CDC requires that a pregnancy-related death satisfy both temporal and casual criteria. A pregnancy-related death is defined as the death of a woman during or within 1 year of pregnancy that was caused by a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy. In contrast, the World Health Organization defines maternal mortality as ''the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.''

The CDC paper compares women of different races, ethnicities and nativity (US or foreign-born) from 1993-2006. They found that for all women, 'the pregnancy-related mortality ratio (PRMR) increased significantly (P<.001) from 11.1 to 15.7 deaths per 100,000 live births from 1993-2006, respectively' (p. 263). Striking differences are found in the overall rate, and the researchers explore the relative effects of age and nativity among racial/ethnic groups. Using US-born white women as the reference group, the study found that those women NOT in this group comprised 62% of the deaths but only accounted for 41% of the live births during this period.

| |

% of deaths

|

% of live births

|

|

US-born White Women (reference)

|

38%

|

59%

|

|

Not US-born White (everyone else)

|

62%

|

41%

|

When the PRMR rates are broken down further, the study found that when compared to US-born white women, only foreign-born white women had a significantly lower risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes (after adjusting for age differences). The table below shows the risk of dying from pregnancy complications among other groups of women compared to US-born white women.

| Women's Nativity and Race |

Risk of dying from pregnancy complications |

| US-born White |

Reference |

| US- and foreign-born Hispanic |

1.1 times higher |

| US- and foreign-born Asian/Pacific Islander |

1.5 times higher |

| Foreign-born Black |

3.6 times higher |

| US-born Black |

5.2 times higher |

The study also found that for 'all groups of women, pregnancy-related mortality ratios increased with age and were especially high for women older than 35 years' (p. 264). For Black women over 35, the PRMR was 99.42, compared to the PRMR for Hispanic (27.20) and White (17.60) women.

Breaking 1993-2006 into two time periods, 1993-1999 and 2000-2006, the study found that the PRMR increased for all groups except for foreign-born Asian/Pacific Islander women, but the increase was statistically significant for only US- and foreign born white women and US-born Black women (30.4%, 29.2%, and 30.4%, respectively; all P<.05).

Also explored in the study are the differences in causes of death for U.S.-born vs. foreign-born women.

The takeaway

'Except for foreign-born white women, all other race, ethnicity, and nativity groups were at higher risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes than U.S.-born white women after adjusting for age differences' (p. 261). The authors suggest that 'integration of quality-of-care aspects into hospital-and state-based maternal death reviews may help identify race, ethnicity, and nativity-specific factors for pregnancy-related mortality,' yet the low numbers of women who die may preclude a full examination of the multiple and complex factors involved in health care provision.

Some suggestive work in this area was published by Tucker and colleagues from the CDC (2007), who examined the prevalence of five conditions considered major causes of mortality occurring during hospitalization for labor, birth and postpartum. They found that African-American women did not have a higher prevalence of these conditions (preeclampsia, eclampsia, abruption placentae, placenta previa and postpartum hemorrhage) compared to other racial/ethnic groups, but were more likely to die from them, suggesting either a possible difference in the severity of the disease or the quality of care provided during hospitalization.

What is needed is a consideration of the birth process, including interventions and the experience of decision-making, as well as the attitudes and behaviors of healthcare clinicians as well as those of childbearing women. Thus, a welcome view into the process of birth comes from a chapter in a book by Eugene Declercq, Mary Barger, and Judith Weiss. In their review, 'Contemporary Childbirth in the United States: Interventions and Disparities,'5 the authors note that public health paradigms have more often focused on antecedents to care (access to contraception and prenatal care) and outcomes (mostly newborn and infant health) with less attention to the processes of care or interventions during the birth itself. While social science research has focused on the context of care systems, there has been little in-depth investigation of the processes of care delivery. Until very recently, there have been no observational studies of U.S. labor and birth in hospital settings since the 1970s.6

As there is little systematic national data to examine patterns of birth process nor any racial-ethnic disparities within them, the authors have examined 'five major interventions used in the birth process: induction, electronic fetal monitoring, epidurals, episiotomy, and cesarean section. We will briefly summarize the existing research on evidence based approaches to promote or prevent certain maternal and/or perinatal outcomes in these areas with an understanding that such research is rarely definitive and, even when it appears to be clear, it may not have a major influence on clinician behavior. We will then examine the distribution of these interventions across different groups, most notably by race/ethnicity. Since parity is such a crucial element in determining birth related behavior, in many cases we will also distinguish the results for primiparous and multiparous mothers.'

Part 2 of this blog post will examine their results and answer the question at the beginning: Are public health and obstetric perspectives providing us with the best paradigms for understanding and reversing disparities in maternal health outcomes?

References

1. Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1998 to 2005. Obstetrics and Gynecology. Dec 2010;116(6):1302-1309.

2. California Department of Public Health. Maternal Death Rates by Race California, 1940-1968.Death Records. Sacramento, CA1968.

3. Creanga AA, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, Callaghan WM. Race, ethnicity, and nativity differentials in pregnancy-related mortality in the United States: 1993-2006. Obstetrics and gynecology. Aug 2012;120(2 Pt 1):261-268.

4. Berg C, Daniel I, Atrash H, Zane S, Bartlett L. Strategies to reduce pregnancy-related deaths: From identification and review to action. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;2001.

5. Declercq E, Barger M, Weiss J. Contemporary Childbirth in the United States: Interventions and Disparities. In: Handler A, al e, eds. Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes: The Evidence from Population-Based Interventions: Springer Science+Business Media; 2011:401-427.

6. Morton CH. Where Are the Ethnographies of US Hospital Birth? Anthropology News. March 2009.

Published: September 07, 2012

Tags

Maternal Mortality RateLamaze EducatorsMaternity CareLabor/BirthMaternal Infant CareLearning OpportunitiesChristine Morton PhDBirth AdvocateAndreea CreangaEugene DeclercqEvidenced based teachingHancs onPractical skillsRacial Disparities In Ma