Root Cause Analysis: Turning a needless maternal death into better care for all

By: Tricia Pil | 0 Comments

On the morning of July 5, 2006, a 16-year-old patient came to St. Mary's Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, to deliver her baby. During the process of her care, an infusion intended exclusively for the epidural route was connected to the patient's peripheral IV line and infused by pump. Within minutes, the patient experienced cardiovascular collapse. A cesarean section resulted in the delivery of a healthy infant, but the medical team was unable to resuscitate the mother. The medication error and its consequences were devastating for the patient's family, the nurse who made the error, and the medical team that labored to save the patient's life.

This is the real story of a tragic and unnecessary maternal death that occurred not in a mud hut in a third world country, nor in a backwater rural health clinic - but in a fully licensed and accredited 440-bed community teaching hospital that delivers more than 3,500 babies annually and serves as a regional referral center for all of south-central Wisconsin. In a highly unusual and commendable move, senior management at St. Mary's requested an outside independent investigation of this event and published their findings in an effort to share painful lessons learned with the medical community and the public.

What happens when an unanticipated maternal death occurs? If the event occurred in a hospital accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations ('Joint Commission'), the hospital must complete a root cause analysis (RCA) as a first step. Since 1996, a total of 84 cases of maternal death have been reported to The Joint Commission. The lessons learned from these most extreme patient care outcomes, also called 'sentinel events,' have widespread implications for everyone involved in maternal and infant care. As William M. Callaghan, M.D., M.P.H., senior scientist in the Division of Reproductive Health at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention remarked, 'Maternal deaths are the tip of the iceberg, for they are a signal that there are likely bigger problems beneath - some of which are preventable,' says Dr. Callaghan. 'It is important to consider the women who get very, very sick and do not die, because for every woman who dies, there are 50 who are very ill, suffering significant complications of pregnancy, labor and delivery.'

What is a root cause analysis?

Root cause analysis, or RCA, is 'a process for identifying the basic or causal factors that underlie variation in performance, including the occurrence or possible occurrence of a sentinel event.' The RCA seeks to answer these questions: What happened? Why did it happen? What will we do to prevent this from happening again? The RCA is not about assigning blame, but rather identifying the direct and indirect contributing factors - latent system errors - that create the 'perfect storm' in which the event occurred.

The RCA process might seem deceptively simple. We may be tempted to approach the RCA in the following manner:

What happened? The patient mistakenly received an IV infusion of epidural medication.

Why did it happen? The nurse hung the wrong IV bag.

What we will do to prevent this from happening again? Fire the nurse.

Indeed, this overly simplistic and ineffective 'shame and blame' approach is the one that many hospitals take in conducting internal investigations of adverse medical events. A more thorough and credible RCA digs at the underlying factors and causes by asking a series of 'Why?' questions, which might look something like this:

What happened?

The patient mistakenly received an IV infusion of epidural medication.

Why did it happen?

The nurse hung the wrong IV bag.

Why did the nurse hang the wrong IV bag?

Because she confused the epidural bag with the IV penicillin bag which were next to each other on the counter.

Why were the bags next to each on the counter?

Because the work flow process included having epidural medications and supplies set up and ready in the room ahead of time.

Why did the work flow process include having analgesia medication in the room ahead of time?

Because anesthesia had in the past expressed dissatisfaction with nursing staff over patients' state of readiness for epidurals.

And,

Why did the nurse hang the wrong IV bag?

Because she confused the epidural bag with the IV penicillin bag.

Why did the nurse get confused?

Because she was tired.

Why was the nurse tired?

Because she had worked two consecutive eight-hour shifts the day before, then slept in the hospital before coming on duty again the following morning.

Why did she work consecutive shifts?

Because she was covering for another colleague and her departure would have left the unit inadequately staffed.

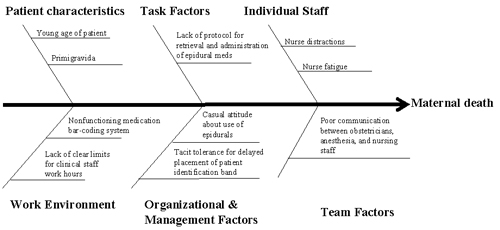

As we repeatedly ask 'Why?' we start to see groups of factors emerge, and these groups can help us to organize our thinking and later, to identify remedies. These groups might include: patient characteristics, task factors, individual staff factors, team factors, work environment, and organizational and management factors. We can map these factors and groups onto a fishbone diagram, a commonly used RCA visual aid:

(Click on graphic for improved viewing)

Now you try it!

Although root cause analyses are most commonly performed in cases of serious permanent physical or psychological harm, we can apply these same principles to 'near-miss' events and instances of suboptimal, although not lethal, care. Read Rima Jolivet's thought-provoking allegorical tale of two births. As you compare the two women's stories, consider the factors that contributed to Karen's negative birth experience. Even if the causes were not stated explicitly in the article, draw upon your own experience as a birthing professional and fill in the gaps. Think about:

- Patient characteristics: Are there pre-existing or co-morbid medical conditions, physical limitations, language and communication barriers, cultural issues, social support needs that play a role?

- Task factors: What protocols and procedures are in place for labor and delivery, for use of analgesia, for dystocia, for C-sections? Are they safe? Are they practical? Are they effective? Are they consistently applied?

- Individual staff: How did the knowledge, skills, training, motivation, and health of Karen's providers affect her care?

- Team factors: How well do the various health care professionals involved in Karen's care work together? What is the nature of the communication? Are there hierarchies? What is the responsiveness of nursing supervisors or attending physicians? How easily can a team member ask for help or clarification?

- Work environment: Is the labor and delivery unit adequately staffed? What is the workload? What happens when the census fluctuates unexpectedly? What is the staffing level of experience, functionality of the equipment, quality of administrative support?

- Organizational and management factors: How do the values of the hospital translate into clinical practice? Do their standards and policies focus more on patient safety and quality of care, or volume and speed? Are management's priorities patient- or provider-centered? Does senior leadership foster a culture of teamwork and safety or blame and shame?

Add your comments below, and I will include them in a root cause analysis of Karen's case in my next blog post.

References:

Jolivet, R. 'Two Birth Stories: An Allegory to Compare Experiences in Current and Envisioned Maternity Care Systems.' Childbirth Connection, 2010.http://www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/allegory_illustrating_vision.pdf

'PS104: Root Cause and Systems Analysis.' Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open School for Health Professions. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/IHIOpenSchool/.

'Sentinel Event Alert: Preventing Maternal Death.' The Joint Commission. Issue 44, January 26, 2010. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/SentinelEventAlert/sea_44.htm

'Sentinel Event Policy and Procedures.' The Joint Commission. July 2007.http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/F84F9DC6-A5DA-490F-A91F-A9FCE26347C4/0/SE_chapter_july07.pdf

Smetzer J, Baker C, Byrne FD, Cohen MR. 'Shaping Systems for Better Behavioral Choices: Lessons Learned from a Fatal Medication Error.' Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010 Apr; 36(4):152-63. http://psnet.ahrq.gov/public/Smetzer-JCJQPS-2010-s4.pdf

Published: November 17, 2010

Tags

SafetyEpiduralsIVsMaternal Infant CareMaternal Death