Perinatal Disparities: Not Just Black and White ~ Part One

By: Darline Turner-Lee | 0 Comments

[Editor's note: Today is part one of a two-part series by Darline Turner-Lee, looking at racial disparities in maternal outcomes. Come back tomorrow to read Darline's discussion on this recent study.]

INTRO: The Financial Burden and Racial Disparities of the US Health Care System

Despite the enormous amount of money the United States spends annually on health care, nearly 17% of the Gross Domestic Product according to www.HealthCare.gov, Americans overall are less healthy and have higher morbidity and higher mortality than many other citizens around the world. Nowhere is this more apparent than in US maternal mortality rates. Amnesty International's Deadly Delivery: The Maternal Health Care Crisis in the USA states,

Maternal mortality ratios have increased from 6.6 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 13.3 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2006. While some of the recorded increase is due to improved data collection, the fact remains that maternal mortality ratios have risen significantly. African-American women are nearly four times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women. These rates and disparities have not improved in more than 20 years.

Researchers have tried to determine what is causing this huge health care disparity between African American women and white women. To try to identify the causative factors, most researchers have compared pregnancy outcomes of African American women and white women living in the same or similar neighborhoods and have attributed much of the disparity to socioeconomic status (SES); i.e. poverty, lack of education, poor access to care. Yet SES alone has not been able to account for the large gap in outcomes. In The Neighborhood Contribution to Black-White Perinatal Disparities: An Example From Two North Carolina Counties, 1999-2001 Ashley Schempf and her colleagues at the US Department of Health and Human Services sought,

"to determine the total contribution of neighborhood inequalities, both observed and unobserved, to the black-white gap in the birth outcomes, low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth (PTB) and small for gestational age (SGA) using hybrid fixed-effects approach to compare only black and white women who lived in the same neighborhoods'

Schempf et al added in the fixed-effects models to better characterize the impact of neighborhood features such as social cohesion and access to goods and services that may vary depending on the racial make up of the neighborhood. Their aim was to compare the results they found with results from conventionally run studies to get a more complete picture of the effect of neighborhood factors on maternal mortality.

Study Population

The study consisted of 31,489 women: 21,221 white women and 10,268 black women. A validated neighborhood deprivation index was used as an indicator of neighborhood SES. The index was constructed from a principle analysis of 8 variables from the 2000 Census of Population and Housing. Individual maternal control factors included age, years of education, marital status, and gravity. Please refer to the tables at the end of this post from the study for demographic data.

Analytic Methods

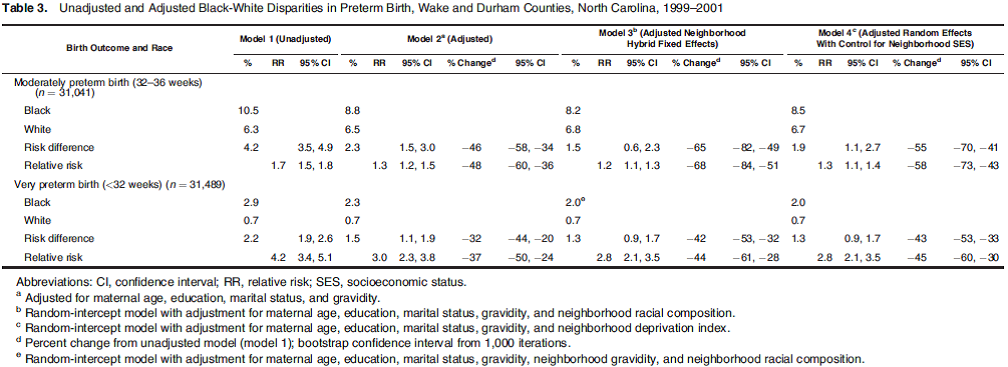

The researchers employed a complex series of statistical analyses to the birth certificate data obtained. For each outcome analyzed, they used 4 logistic models to determine 1) The total contribution of neighborhood to the racial disparity and 2) To compare the performance of a neighborhood fixed-effects estimator with the simple control for neighborhood SES (the standard analysis method). Model 1 was an unadjusted logistic that measured the difference of race on maternal outcomes. Model 2 was an adjusted logistic that controlled for individual maternal characteristics. Model 3 was a hybrid fixed-effect model that accounts for all between neighborhood variation in risk that is associated with race and provides a within-neighborhood race contrast. This model controlled for the excess odds of an adverse outcome associated with living in a neighborhood with a higher proportion of black births. Finally, Model 4 controlled for neighborhood SES. (Please refer to the actual study for statistical equations).

Results

The authors noted clear differences in sociodemographic characteristics and neighborhood deprivation. Black women were at least twice as likely to deliver LBW, preterm and SGA infants as white women. When data was adjusted for race and neighborhood deprivation, the disparities were reduced. With all confounding variables controlled for by the fixed effect analyses PTB was the only adverse outcome that continued to have higher adverse outcomes. The disparities in PTB persisted even when parceled out for Moderate preterm birth (MPTB) 32-36 weeks gestation and Very preterm birth (VPTB) <32 weeks gestation. The absolute risk of MPTB was nearly twice that of VPTB while the relative risk of VPTB was much greater than that of MPTB. Based on this data, the authors believe that there are other significant yet unobserved neighborhood contributions to disparities for preterm birth. The results are presented in the tables below.

*Click here to jump to part two of this series.

Posted by: Darline, Turner-Lee, BS, MHS, PA-C

Published: November 01, 2011

Tags

PregnancyUnited States Maternal MortalityLamazeDarline Turner LeeMaternal mortalityOnline StoreAshley SchempfMaternal Outcomes By RaceMaternal Outcomes By Socioeconomic StatusRacial Disparities In Maternal Mortality