Part 2: Pain, Suffering, and Trauma in Labor and Subsequent Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Practical Suggestions to Prevent PTSD After Childbirth

By: Penny Simkin, PT, CD(DONA), CCE | 0 Comments

[Editor's note: This is part two of Ms. Simkin's post on childbirth-related Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The post is long and detailed - every word worth reading. Set aside ample time to read this article: such that devouring, versus skimming, might be accomplished. Birthing mothers & their birth partners, doulas, childbirth educators, L&D staff and maternity care providers will ALL benefit from the recommendations provided below. To read part one of the post, go here.]

With Part 2 of this blog post, I'd like to move toward practical applications of the research findings on variables associated with traumatic birth and PTSD, as described in Part 1. Here is a list of suggestions (much more lengthy that I originally anticipated - Sorry!) for caregivers, doulas and childbirth educators, designed to prevent or minimize traumatic childbirth and subsequent PTSE of PTSD. These include suggestions for before, during and after childbirth.

Checklist for before labor:

Identify the woman's issues or fears relating to childbirth.

The caregiver should elicit a psychosocial and medical history from the woman, and if there is evidence of previous unresolved trauma, discuss and strategize a course of care that maximizes her feelings of being supported, listened to, and in control of what is done to her, and minimizes the likelihood of loneliness, disrespect, and excessive pain. (1, 2)

The unique non-clinical relationship between doula and client requires that doulas do not ask specific questions regarding the woman's psychosocial and medical history; rather, an open-ended question such as 'Do you have any issues, concerns or fears that you'd like to tell me to help me provide better care for you?' The woman then has the option of whether or not to disclose sensitive issues. Many doulas, however, can recognize strong emotions without knowing specifics. The doula tries to be sensitive and accommodating without discussing her client's anxiety directly.

Childbirth educators, rather than asking their groups about their issues, may find it more appropriate to discuss the potential effects of anxiety or old trauma on women's experiences of labor, and to provide resources: books, referrals to support groups or counselors (possibly including the educator herself, if she can provide counseling) that can be helpful. Caution: If offering her services for counseling, the educator may be perceived as having a conflict of interest in raising these issues. To avoid such a conflict, I advise against charging a fee (beyond the class fee) for counseling one's students, or to avoid mentioning herself as a resource.

The purposes of counseling for a woman with negative feelings about childbirth or maternity care are to help her clarify and address these feelings and strategize ways to 1) reduce their negative impact (at least), or 2) prevent further suffering or retraumatization, and 3) even result in empowerment and healing for the woman. (3) In fact, I feel there's a great need to increase the numbers of birth counselors - people with a deep knowledge of birth and its accompanying emotions; maternity care practices and local options; excellent communication skills; and an understanding of trauma, PTSD, and other mood disorders relating to childbearing. Wise childbirth educators and doulas with good communication skills should consider expanding their roles in this direction, along with nurses and midwives who have the time and skills to provide such counseling.

Recommend that the woman/couple learn about labor, maternity care practices, and master coping techniques for labor.

Childbirth classes that emphasize these elements, especially when they assist women and couples in personalizing their preferences and ways of coping with pain and stress, can take many surprises out of labor and empower parents to participate in their care and help themselves deal with pain and stress, whether with or without pain medications or other interventions.(4)

Recommend a Birth Plan:

A birth plan is a document that describes the woman's personal values, preferences, emotional needs or anxieties regarding her child's birth and her maternity care. It is most useful if it is the result of collaborative discussion between the woman and her caregiver, and if it is placed in the woman's medical chart to be accessible for all who are involved in her care. (5) Usually, in hospitals where there is a spirit of cooperation and good will between clients and staff, birth plans are easily accommodated. Sometimes, as in some cases of previous trauma or other adverse events, a woman will have a greater need for special considerations than other women. If the effort is made with care planning to address those needs, the potential for a safe satisfying birth experience is great, without causing harm or overwork for the staff. For example, simple requests (such as having people knock and identify themselves before entering her room; limiting the number of routine vaginal exams to those that are necessary for a clinical decision; allowing departure from a routine such as forceful breath holding and straining for birth) require flexibility but are not dangerous. A woman is likely to feel respected and understood if the staff gives serious consideration to her requests. The birth plan should include her preferences for the use of pain medications, not only yes or no, but the degree of strength of her preferences (6)

Of course, in her birth plan (or another term instead of 'plan' may be used), she should use polite and flexible language (couching her preferences in language such as 'as long as the baby is okay,' 'if no medical problems are apparent'). She might prepare a Plan A, for a smooth uncomplicated labor, and a Plan B, for unexpected twists that make intervention necessary. A birth plan allows everyone to be on the same page, and ensures that the woman has a voice in her care, even when she is in the throes of labor. Childbirth educators and doulas have a responsibility to guide parents in the language and options included in the birth plan to maximize the likelihood that the plan will be well-received, while still reflecting her needs and wishes. If prenatal discussions indicate the birth is unrealistic or unreasonable, there is opportunity to discuss, clarify, and settle the problems before labor, when it's too late.

During labor:

Those caring for laboring women should remind themselves that the birth experience is a long-term memory (7) that can be devastating, negative, depressing, acceptable, positive, empowering, ecstatic, or orgasmic.

The difference between negative and positive depends not only on a healthy outcome, but a process in which she was respected, nurtured, and aided. In a study that I published years ago, on the long-term impact of a woman's birth experience, I found that the most influential element in women's satisfaction (high or low) with their birth experience 15 to 20 years later is how they remember being cared for by their clinical care providers (8), In fact, it was that study that motivated me to do what I could to ensure that women receive the kind of care that will give them lifelong satisfaction with their birth experiences. The answer became the doula.

'How will she remember this?' is a question that everyone who is with a laboring woman should ask him or herself periodically in labor, and then be guided by the answer to say or do things that will contribute to a good memory.

The doula:

The research findings of the benefits of the doula are well-known; in fact, a newly updated Cochrane Review of the benefits of doulas once again demonstrates the unique contribution of continuous support by a doula in improving numerous birth outcomes (See press release athttp://www.childbirthconnection.org/pdfs/continuous_support_release_2-11.pdf and the full review with a summary at www.childbirthconnection.org/laborsupportreview/ (9). Besides the benefits reported in the Cochrane Review, I'd like to suggest a benefit that doulas may confer when traumatic birth is occurring: the doula's care may be instrumental in preventing a traumatic birth from developing into PTSD. Czarnocka and Slade found with their study on normal births, 24% of the women had Post-traumatic Stress Effects (PTSE) and 3% had the full syndrome of PTSD.(10) (See Part 1 of this blog post for an explanation of the difference between PTSD and PTSE). They found that the women with PTSD were more likely to have felt unsupported and out of control than those who had PTSE. PTSE is far less serious that PTSD in terms of duration and spontaneous recovery.

Ironically, doulas are often traumatized by what they witness in birth settings where individualized care and low intervention rates for normal birth are not emphasized or supported. (11) They feel frustrated, demoralized or burned out, especially when their clients who had originally expressed a preference for minimal intervention, seem oblivious to the departure from their stated preferences and even grateful to the doctor who 'saved their baby' after unnecessary interventions (which the woman had not wanted in the first place) led to the need for a cesarean. The woman has a traumatic birth, but later seems okay with everything that happened and doesn't seem to have many serious leftover trauma symptoms (PTSE). I feel certain that in some of these cases of PTSE, the doula, by remaining with the woman, nurturing and helping her endure the physical helplessness, the fear and worry for her baby and herself, may have provided the positive factors identified by Czarnocka and Slade that protected her from PTSD. Prevention of PTSD is a worthy goal for a doula when birth is traumatic. (12)

Code word to prevent suffering:

No one wants a woman to suffer during labor. On the other hand, no supportive person wants a woman to have pain medication that she had hoped to avoid. A previously agreed-upon 'code word' provides a safety net for a woman who is highly motivated to have an unmedicated birth. She says her code word only when she feels that she cannot go on without medical pain relief. The code word frees the woman to complain, vocalize, cry, and even to ask for medications, but her support team knows to continue their pep talks and encourage her to continue, and suggest some other coping techniques. However, if she says her code word, her team quits all efforts to help her continue without pain medications and turns to helping her get them. (13)

Why is a code word better than continuing to help her cope without medications when a woman (who had felt strongly about avoiding them) says she can't go on, or vocalizes her pain loudly? It's because some women cope better if they can express their pain than to have to act as if it doesn't hurt. It also guides the team much more clearly than her behavior. As one woman said, 'I shouted the pain down!' It's really important for the nurse to know and understand the purpose of the code word, or she'll feel the team is being cruel. If a supporter wonders if the woman forgot her code word, he or she can remind the woman, 'You have a code word, you know.' One woman, when reminded, asked herself, 'Am I suffering?' She decided she wasn't, and went on to have a natural birth.

Of course, a code word is unnecessary if the woman plans to use an epidural.

Pain Rating Scale and Coping Scale:

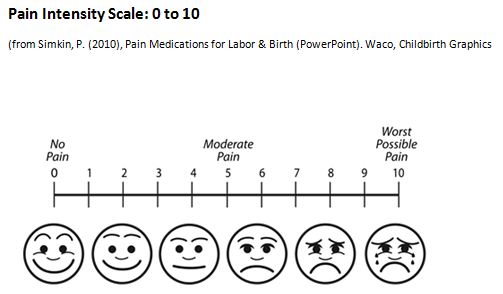

All hospitals use a Pain Intensity Scale to measure patients' (including laboring women's) pain. See illustration of the Pain Intensity Scale. The goal, of course, is to ensure that no one suffers. The scale doesn't rate suffering, however, since pain and suffering are not the same. (See Part 1 of this blog post.) Much more important is the woman's ability to cope. See the illustration of the Pain Coping Scale. If she rates her pain at 8 (very high) and her coping is also rated very high, she's not suffering. If pain is at 8 and coping is at 2, she could be suffering, and obviously needs attention, assistance, and very likely, pain medication.

Assessing a woman's coping is done differently than assessing her pain. Rather than asking her to rate her coping on a scale of 10 (coping most easily) to 0 (total inability to cope), the supporter observes her behavior for the 3 Rs: Relaxation (between, if not during, contractions); Rhythm (in movements, breathing, moaning) and Ritual (coping with the same rhythmic activity for many contractions in a row). If she does not maintain the 3 Rs, she might very well suffer and feel traumatized by her labor. (14)

Pain Coping Scale: 10 to 0

A second way to assess coping is to ask the woman, after a contraction, 'What was going through your mind during that contraction?' If her answer focuses on positive thoughts, or helpful activities, she is coping. If she focuses on how long or difficult it is, or how tired or discouraged, or how much pain she feels, she is not coping well and may be suffering. (15)

Intensive labor support may help her cope better and keep her from suffering, but pain medication may be the best way to relieve unmanageable pain that causes suffering. Help her obtain effective pain relief, whether it is pharmacological or non-pharmacological, according to her prior wishes and the present circumstances.

Recognize that if she has an epidural, she still needs emotional support and assistance with measures to enhance labor progress and effective pushing.

The absence of pain, usually accomplished so effectively by the epidural, does not mean absence of suffering. Nurses and caregivers in hospitals with high epidural rates are likely to make comments like, 'There's no need to suffer;' 'You don't have to be a martyr;' 'There's nothing to prove here.' With this assumption that pain and suffering are the same, once the pain is eliminated, the woman's emotional needs are often neglected. In their classic study of pain, coping and distress in labor, with and without epidurals, Wuitchik and colleagues found, 'With epidurals, pain levels were reduced or eliminated. Despite having virtually no pain, these women also engaged in increased distress-related thought during active labor. The balance of coping and distress-related thought for women with epidurals was virtually identical to that of women with no analgesia.' (16)

What are women distressed about when they have no pain? Wuitchik and colleagues named many things (and I have added some that I have witnessed), including: the length of labor; numbness; side effects such as itching and nausea; being left alone by supporters when she was 'comfortable;' helplessness; passivity; worries over the baby's well-being (especially with the sudden and dramatic reactions of staff when the mother's blood pressure and fetal heart rates dropped); or feeling incompetent (when unable to push effectively despite loud directions to push long and hard).

The point is that women may suffer even if they have no pain, and their needs for continuing companionship, reassurance, kind treatment, assistance with position changes and pushing, attention to their discomforts and their emotional state, remain as important to the woman's satisfaction and positive long-term memory as they are to the unmedicated woman. (17)

Take note if any variables occur during labor that are associated with traumatic births and PTSE (explained in Part 1 of this blog).

Warning signs of potential PTSE includefeeling: angry (blaming others, alone, unsupported, helpless, overwhelmed, or out of control; also panicking, dissociating, giving up, feeling hopeless and as if she can't go on ('mental defeat'). If she exhibits some of these signs, her caregiver, doula, and others should do as much as possible to prevent the trauma from becoming PTSD later (remaining close to her, reassuring her when possible, helping her keep a rhythm through the tough times, explaining what's happening and why, holding her, making eye contact and talking to her in a kind firm confident tone of voice). The point is to help her maintain some sense that she is not totally alone, out of control, and overwhelmed.

After the Birth

Seeds of accomplishment

Before leaving the birth, a few specific positive and complimentary words from the 'expert,' her doctor midwife or nurse, will remain in her mind, as she ruminates on her traumatic birth. 'I was so impressed when you said you wanted to try waling when the labor had stalled for so long;' or 'when you said you wanted to push a little longer;' or 'when you realized that we had to get the baby out right away, and you said, 'do what you have to do.''

Anticipatory guidance for after birth.

When her labor and birth were traumatic, it is wise for the caregiver and her team to

- Acknowledge it openly: 'You certainly did your part. I just wish it had gone more as you had hoped.'

- Anticipate some ways she might feel later, for example, she may find herself thinking a lot about the birth and recalling her feelings at the time.

- Give guidance on what to do: she can call her care provider, doula, childbirth educator, a good friend, or a counselor to review and debrief the experience (3, 18, 19, 20, 21). This cannot be rushed and the counselor (caregiver, doula, or other) should be available when the woman is ready to discuss it.

- Books (22, 23, 24) articles (surf the web!), and Internet support groups may be helpful: Check the following:

http://www.birthtraumaassociation.org.uk/; http://solaceformothers.org/mothers-forum.html; http://www.tabs.org.nz/.

- Believe the woman when she says her birth was traumatic, and accept her perceptions of the events before clarifying or correcting misinterpretations. Help her reframe the event more positively, if possible, or suggest therapeutic steps to recover from the trauma. If PTSD does result, a referral should be made to a trauma psychotherapist, preferably one with experience with maternal mental health issues.

In conclusion, this is a reminder that traumatic childbirth is all too common, but with personalized sensitive care, much birth trauma can be avoided. If birth is traumatic for the woman, there are steps that can be taken before, during, and after childbirth to help ensure that the trauma does not become Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In fact, processing a traumatic birth experience can even provide an opportunity to heal and thrive afterwards.

This blog post series will be featured in the Fall 2011 issue of the Journal of Perinatal Education. For references, please contact Ms. Simkin directly at: penny@pennysimkin.com or reference the JPE issue: Summer 2011 Volume 20, Number 3.

Posted by: Penny Simkin, PT, CCE, CD(DONA)

Published: February 27, 2011

Tags

Childbirth educationHealthy Birth PracticesBirth TraumaPenny SimkinLabor/BirthMaternal Infant CareDoula CareCheck List For DoulasChildBirth Related PTSDHhow To Avoid Birth TraumaHow To Have The Best Birth