It Takes a Professional Village! A Study Looks At Collaborative Interdisciplinary Maternity Care Programs on Perinatal Outcomes

By: Sharon Muza, BS, LCCE, FACCE, CD/BDT(DONA), CLE | 0 Comments

The Canadian Medical Association Journal, published in their September 12, 2012 issue a very interesting study examining how a team approach to maternity care might improve maternal and neonat aloutcomes. The study, Effect of a collaborative interdisciplinary maternity care program on perinatal outcomes is reviewed here.

The Challenge

Photo Source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jstownsley/28337593/

The number of physicians in Canada who provide obstetric care has declined in past years for reasons that include increasing physician retirement, closure of rural hospitals, liability concerns, dissatisfaction with the lifestyle and a difficulty in accessing maternity care in a variety of settings. While registered midwife attended births may be on the rise, midwives in Canada attend less than 10% of all births nationwide. At the same time as the number of doctors willing or able to attend births decline, cesarean rates are on the rise, causing pressure on the maternity care system, including longer hospital stays both intrapartum and postpartum, which brings with it the associated costs and resources needed to accommodate this increase.

The diversity of the population having babies in many provinces is increasing, presenting additional challenges in meeting the non-French/English speaking population, who are more at risk for increased obstetrical interventions and are less likely to breastfeed.

The Study

In response to these challenges, the South Community Birth Program was established to provide care from a consortium of providers, including family practice physicians, community health nurses, doulas, midwives and others, who would work together to serve the multiethnic, low income communities that may be most at risk for interventions and surgery.

The retrospective cohort study examined outcomes between two matched groups of healthy women receiving maternity care in an ethically diverse region of South Vancouver, BC, Canada that has upwards of 45% immigrant families, 18% of them arriving in Canada in the past 5 years. One group participated in the South Community Birth Program and the other received standard care in community based practices.

The South Community Birth Program offers maternity care in a team-based shared-care model, with the family practice doctors, midwives, nurses and doulas working together . Women could be referred to the program by the health care provider or self refer. After a few initial standard obstetrical appointments with a family practice doctor or midwife occur to determine medical history, physical examination, genetic history, necessary labs and other prenatal testing, the women and their partners are invited to join group prenatal care, based on the Centering Pregnancy Model. Approximately 20% of the first time mothers choose to remain in the traditional obstetric care model. 10-12 families are grouped by their expected due date, and meet for 10 scheduled sessions, facilitated by either a family physician or midwife and a community nurse. Each session has a carefully designed curriculum that covers nutrition, exercise, labor, birth and newborn care, among other topics. Monthly meetings to discuss individual situations and access to comprehensive electronic medical records enhanced the collaboration between the team. Trained doulas, who speak 25 different languages, also meet with the family once prenatally and provide one on one continuous labor support during labor and birth. The admitting midwife or physician remains in the hospital during the patient's labor and attends the birth.

After a hospital stay of 24-48 hours, the family receives a home visit from a family practice physician or midwife the day after discharge. Clinic breastfeeding and postpartum support is provided by a Master's level clinical nurse specialist who is also a board certified lactation consultant. At six weeks, the mother is discharged back to her physician, and a weekly drop in clinic is offered through 6 months postpartum.

The outcomes of the women in the South Community Birth Program were compared to women who received standard care from their midwives or family practice physicians. Similar cohorts were established of women carrying a single baby of like ages, parity, and geographic region, and all the mothers were considered low risk and of normal body mass index.

The primary outcome measured was the proportion of women who underwent cesarean delivery. The secondary outcomes measured were obstetrical interventions and maternal outcomes (method of fetal assessment during labor, use of analgesia during labor, augmentation or induction of labor, length of labor, perineal tramau, blood transfusion and length of stay) and neonatal outcomes (stillbirth, death before discharge, Apgar score less than 7, preterm delivery, small or large for gestational age, length of hospital stay, readmission, admission to neonatal intensive care unit for more than 24 hours and method of feeding at discharge).

Results

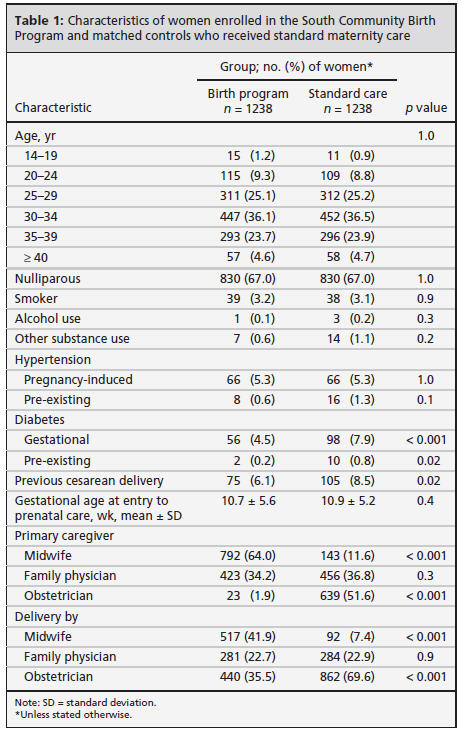

There was more incidence of diabetes and previous cesareans in the comparison group but the level of alcohol and substance use was the same in both groups. Midwives delivered 41.9% of the babies in the birth program and 7.4% of babies in the comparison group.

When the rate of cesarean delivery was examined for both nullips and multips, the birth group women were at significantly reduced risk of cesarean delivery and were not at increased risk of assisted vaginal delivery with forceps or vacuum.

Interestingly, the birth program women who received care from an obstetrician were significantly more likely to have a cesarean than those receiving in the standard program who also received care from an obstetrician. More women in the birth program with a prior cesarean delivery planned a vaginal birth in this pregnancy, though the proportion of successful vaginal births after cesareans dd not differ between the two groups.

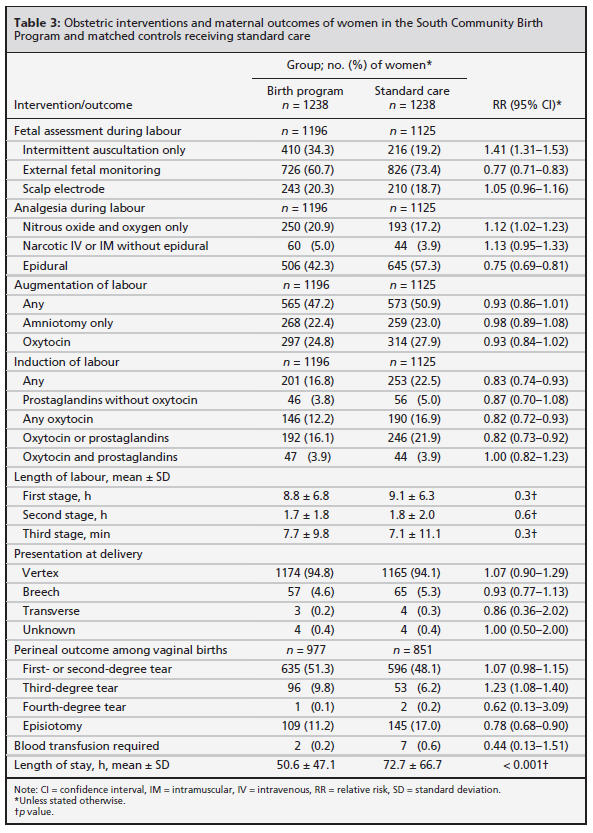

The women in the community birth program experienced more intermittent auscultation vs electronic fetal monitoring and were more likely to use nitrous oxide and oxygen alone for pain relief and less likely to use epidural analgesia (Table 3). Though indications for inductions did not differ, the birth program women were less likely to be induced. More third degree perineal tears were observed in the birth program group but less episiotomies were performed. Hospital stays were shorter for both mothers and newborns in the community program.

When you look at the newborns in the birth program, they were at marginally increased risk of being large for gestational age and were readmitted to the hospital in the first 28 days after birth at a higher rate, the majority of readmissions in the community and standard care group were due to jaundice. Exclusive breastfeeding in the birth program group was higher than in the standard group.

Discussion

The mothers and the babies in the community birth program were offered collaborative, multidisciplinary, community based care and this resulted in a lower cesarean rate, shorter hospital stays, experienced less interventions and they left the hospital more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding. Many of the outcomes observed in this study, especially for the families participating in the South Birth Community Program are in line with Lamaze International's Healthy Birth Practices. There are many questions that can be raised, and some of them are are discussed by the authors.

Was it the collaborative care from an interdisciplinary team result in better outcomes? Was there a self-selection by the women themselves for the low intervention route that resulted in the observed differences? Are the care providers themselves who are more likely to support normal birth self-selecting to work in the community birth program? Did the fact that the geographic area of the study had been underserved by maternity providers before the study play a role in the outcomes? Did the emotional and social support provided by the prenatal and postpartum group meetings facilitate a more informed or engaged group of families?

I also wonder how childbirth educators, added to such a model program, might also offer opportunity to reduce interventions and improve outcomes Could childbirth educators in your community partner with other maternity care providers to work collaboratively to meet the perinatal needs of expectant families? Would bringing health care providers interested in supporting physiologic birth in to share their knowledge in YOUR classrooms help to create an environment where families felt supported by an entire skilled team of people helping them to achieve better outcomes.

Would this model be financially and logistically replicable in other underserved communities and help to alleviate some of the concerns of a reduction in obstetrical providers and increased cesareans and interventions without improved maternal and newborn outcomes? And how can you, the childbirth educator, play a role?

References

Azad MB, Korzyrkyj AL. Perinatal programming of asthma: the role of the gut microbiota. Clin Dev Immunol 2012 Nov. 3 [Epub ahead of print].

Canadian Association of Midwives. Annual report 2011. Montréal (QC): The Association; 2011. Available: www .canadianmidwives.org /data/document /agm %202011 %20inal .pdf

Farine D, Gagnon R; Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Are we facing a crisis in maternal fetal medicine in Canada? J'Obstet Gynaecol-Can 2008;30:598-9.

Getahun D, Oyelese Y, Hamisu M, et al. Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption.Obstet-Gynecol 2006;107:771-8.

Giving birth in Canada: the costs. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute of Health Information; 2006.

Godwin M, Hodgetts G, Seguin R, et al. The Ontario Family Medicine Residents Cohort Study: factors affecting residents' decisions to practise obstetrics. CMAJ 2002;166:179-84.

Hannah ME. Planned elective cesarean section: A reasonable choice for some women? CMAJ 2004;170:813-4.

Harris, S., Janssen, P., Saxell, L., Carty, E., MacRae, G., & Petersen, K. (2012). Effect of a collaborative interdisciplinary maternity care program on perinatal outcomes. Canadian Medical Association Journal, doi: DOI:10.1503 /cmaj.111753

Ontario Maternity Care Expert Panel. Maternity care in Ontario 2006: emerging crisis, emerging solutions: Ottawa (ON): Ontario Women's Health Council, Ministry of Health and LongTerm Care; 2006.

Reid AJ, Carroll JC. Choosing to practise obstetrics. What factors influence family practice residents? Can Fam Physician 1991; 37:1859-67.

Thavagnanam S, Fleming J, Bromley A, et al. A meta-analysis of the association between cesarean section and childhood asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38:629-33.

Published: September 19, 2012

Tags

PregnancyBreastfeedingChildbirth educationInductionCesareanInterventionsHealthy Birth PracticesMidwivesHospitalsNewbornsMaternity Care SystemsEpiduralsMaternal Infant CareMDMaternity Care QualityCanadaSouth Community Birth Prog